This article is authored by Samantha Eisert and Danny Rahal and is part of the 2020 pre-graduate spotlight series.

We live within a complex social hierarchy where access to resources is unequal, and the richest people with the most resources and respect are considered to be at the top of the hierarchy and the poorest people with the least resources and respect are at the bottom. Some people have more access to resources that others and it is our socioeconomic status that defines our placement in this hierarchy. Socioeconomic status is determined by combining ones financial, social, and educational resources. Humans are quite good at both displaying their own and judging others’ socioeconomic status by looking at the car they drive, the clothes they wear, and the people they surround themselves with.

However, perhaps where you view yourself in society surpasses objective levels of income and assets when social standing is in question. Maybe a college student has a fairly high socioeconomic status compared to the rest of the United States but they see themself as being of much lower status because they do not have the same luxuries as their friends, neighbors, or coworkers—this is their subjective social status (SSS). In addition to objective indices, people develop a sense of SSS, or their perception of their own rank in society, which transcends socioeconomic status in predicting health outcomes (1). SSS takes into account one’s socioeconomic status but also asks where one feels they stand in the social hierarchy. This means SSS is largely determined by how a person compares their resources and rank to those around them—after being the judge of other people’s status. As an example, achieving a college education is an achievement that objectively places people at higher social status. However, going to a school where everyone is high achieving can make people feel relatively lesser such that they have lower SSS relative to peers.

Wealthy people—those with higher socioeconomic status—are healthier than those of lower status. SSS is also robustly related to health even after the objective measures of socioeconomic status are controlled for. Therefore, merely feeling that you are a higher status relative to others enhances your health. Past studies relating SSS to health are correlational in that they simply rate one’s SSS and heath and determine if they are related in a positive or negative way. This can be tricky because oftentimes there are other variables (like access to healthcare) that also affect one’s health in a positive or negative way. Consequently, researchers have looked to manipulating social status by assigning participants to high or low status in an experimental setting in order to determine if SSS affects health.

People of higher status tend to have more power and therefore have the necessary resources to fall back on when they face adverse situations (2). For instance, if a well-off person were to have car troubles it would be an unfortunate inconvenience for them, but they would have the resources to get it fixed and drive a rental in the meantime. On the other hand, if a person of lower standing were to have a broken-down car, they may not be able to afford to get it fixed in a timely manner and this may make them unable to get to work or other obligations. It would have greater repercussions for them and their overall longevity. Therefore, people of high SSS tend to perceive difficult situations as challenging rather than threatening because they know they will be able to cope regardless of the outcome. Contrastingly, people of low SSS tend to view difficult situations as more threatening because, usually, more of their resources are at stake if a negative outcome were to result (3).

Social standing is embedded in society, so how can we test the effects of status specifically? Researchers conducted two studies in order to test the hypothesis that higher SSS is linked to better physiological health and well-being. In one study, 81 male police officers rated their local SSS (in relation to other officers at their station) and distal SSS (in relation to the broader U.S. population) and completed a stressful task, during which the researchers measured their physiology as an index of their stress responses.

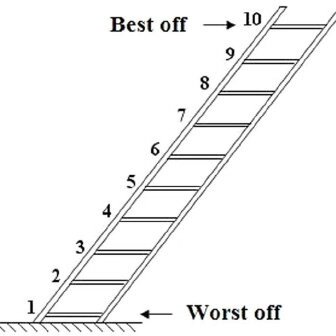

To measure SSS, participants typically view a ladder with ten rungs and mark where they view themselves on the ladder relative to the “worst off” people at the bottom and the “best off” people at the top (4; see figure 1 below). With two of these ladders, the participants compared themselves to other people at the police department on one ladder and people in the U.S. more broadly on the other. Then, the officers underwent a Trier social stress task—a validated procedure used in research to evoke social-evaluative stress in participants—that was altered to fit their profession. In their specific stress task, they were faced by an aggravated citizen (an actor) claiming to be treated unfairly by another officer. The participant policeman was instructed to gather information and calm the citizen, all while being evaluated by the researchers pretending to be skilled evaluators. Imagine dealing with a sensitive situation like this, and now imagine doing so while being evaluated by a group of strangers who are specifically judging how good you are at your job.

After undergoing the experiment, the officers who reported a higher SSS at the police station (being closer to the best-off people) initially rated the task as more challenging and less threatening than police officers who had lower SSS and therefore had a more adaptive stress reaction based on their physiological profiles of testosterone and heartrate. Testosterone was measured because it is known to rise in response to dominance, power, and attempts to maintain or gain status (5). Heart rate was also measured because it is a physiological signal that can differentiate challenge and threat states—heart rate increases in both challenge and threat responses to stress, but increases more in response to challenge. Greater heart rate reactivity can also be a signal of better overall health. This might be a little counterintuitive, since higher heart rate is normally a concern for health. However, during stressful situations the body needs to mobilize resources and energy to ensure survival. Greater heart rate responses to threat suggest that the body is better able to respond to situations accordingly.

Participants of high SSS showed testosterone levels and heart rate increase from participation in the task more significantly than those of low SSS. Therefore, the participants of higher SSS were responding to the stressor in a more healthy and adaptive way. As predicted from past research, this effect was only found for local status relative to other police officers—not status relative to society in general. This finding suggests that status relative to peers and close others may be especially important for health.

Was higher SSS the reason for greater increases testosterone and heart rate in these participants? To find out, researchers had to dig deeper and conduct a second study where they could manipulate SSS in order to assess how the different stress systems of the body responded. In their second study, 84 college student participants were asked to work on a task with another “participant partner” (an actor who was actually part of the research team). The participant began by filling out a questionnaire and then the participant and actor were randomly assigned to be either a higher status “leader” or a lower status “support” person. In separate rooms the participant and actor were connected via video chat and told that their responses to the personality questionnaires they filled out when they arrived had determined their role assignment of “leader” or “support”. Their first task was to record a speech (for their partner to watch) for why they believed they were assigned their role. For their next task, they were brought into the same room and asked to enact their roles of “leader” and “support” and work together to complete puzzles on a video game. Reflecting on their task, participants assigned to lower status viewed their “leaders” as being less competent. In contrast, high status participants who were assigned to be leaders viewed their “supporters” more favorably.

With respect to physiology, the researchers measured testosterone and heart rate again. However, they also added more refined measures of the two branches of the autonomic nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system is our body’s response to “fight or flight” and researchers measured it by looking at the pre-ejection period decrease from baseline. The parasympathetic nervous system is our body’s “rest and digest” system and was measured by looking at the decrease in heart rate variability in participants. When actively engaged with a stressor, people tend to show greater reactivity in both systems—they show greater sympathetic nervous system activity and lower parasympathetic nervous system activity. People tend to engage with situations they find challenging rather than situations they find threatening. This response tends to be adaptive. For example, when a student is taking an exam they feel well prepared for, their body’s resources are mobilized to engage and focus in on the test. They are focused on the test and answering the questions as quickly as possible, so their heart is beating faster. On the other hand, if a student did not study, when they go to take the exam they may give up and disengage, and their body will not show this physiological arousal.

Consistent with the researchers’ first study, when completing the task, higher status participants had a greater increase in testosterone and heart rate from baseline compared to lower status. These findings again suggest that high SSS promotes appraising tasks as challenging rather than threatening by showing greater physiological responses. Interestingly, the researchers also found that high SSS related to greater sympathetic and parasympathetic reactivity. This profile of physiological response may have implications for health. This greater sympathetic and parasympathetic reactivity has been linked with better mental health and lower risk for depression (6,7). This experiment revealed that the mere perception of having higher status relative to others influenced physiological responses to threat. Further, feeling of higher status promoted physiological responses that are linked with better psychological and physiological health.

Taken together, this research demonstrates that higher SSS individuals seem to react to stress in more efficient ways than people of lower SSS. Furthermore, SSS with respect to local peers seems more related to stress than SSS with respect to society in general. Could differences in stress interpretation be one mechanism explaining the long-term health benefits of high status? If mere perceptions or feelings of having higher status than others can influence our physiology and cognitions, can we identify ways to make people feel of higher status relative to others? Does rhetoric that causes some groups to feel of lower status potentially influence their physiology and health? Does our health really depend on how we respond to the stressors in our life? If feeling of higher status relative to others can shape physiology and cognitive responses to stress, perhaps we can create interventions that improve people’s health and ability to respond to stress by targeting their perceptions of status. This research offers some evidence for how your perceived social standing impacts your life in immensely important ways. Next time you compare your home, car, or job to your neighbor’s perhaps it is worthwhile to take a step back and ponder if these status comparisons are beneficial to your health. If we can lessen our comparisons to one another or learn to be grateful for what we have rather than compare ourselves with those who are better off, as a society we may see a tremendous rise in well-being—especially when it comes to the coping with stressful situations.

References

1. Rahal, D., Chiang, J. J., Bower, J. E., Irwin, M. R., Venkatraman, J., & Fuligni, A. J. (2019). Subjective social status and stress responsivity in late adolescence. Stress, 1-10.

2. Magee, J. C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). 8 social hierarchy: The self‐reinforcing nature of power and status. Academy of Management annals, 2(1), 351-398.

3. Blascovich, Jim, and Wendy Berry Mendes. “Social psychophysiology and embodiment.” Handbook of social psychology 1 (2010): 194-227.

4. Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy, White women. Health psychology, 19(6), 586.

5. Schultheiss, O. C., & Rohde, W. (2002). Implicit power motivation predicts men’s testosterone changes and implicit learning in a con- test situation. Hormones and Behavior, 41, 195–202.

6. Graziano, P., & Derefinko, K. (2013). Cardiac vagal control and children’s adaptive functioning: A meta-analysis. Biological psychology, 94(1), 22-37

7. Schiweck, C., Piette, D., Berckmans, D., Claes, S., & Vrieze, E. (2019). Heart rate and high frequency heart rate variability during stress as biomarker for clinical depression. A systematic review. Psychological medicine, 49(2), 200-211.